Author:

Kai Knudsen

Granskare:

Sven Erik RickstenUpdated:

18 January, 2026

Here is a description of thoracic anesthesia with sections on anesthesia for coronary artery surgery, anesthesia for lung surgery including double-lumen tube, anesthesia for patients with heart disease, and management of various types of cardiac valvular disease. It also covers GUCH and its impact on the choice of anesthesia form, as well as different types of pacemakers.

- Cardiothoracic Anesthesia

- Cardiac Chambers and Valves

- Anesthesia for Aortic Stenosis

- Anesthesia for Aortic Regurgitation

- Anesthesia for Mitral Stenosis

- Anesthesia for Mitral Regurgitation

- Tricuspid Regurgitation

- Cardiac Tamponade

- Echocardiography

- Anesthesia for Coronary Surgery

- Guidelines for Revascularization in Stable Coronary Artery Disease

- Thoracic Surgery and Thoracic Anesthesia

- Anesthesia for Coronary Surgery

- Anesthesia for the Cardiac Patient

- Perioperative Management of Heart Failure

- Diastolic heart failure

- Anesthesia in pulmonary hypertension

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Aortic stenosis

- Aortic insufficiency

- Mitral Valve Stenosis

- Mitral Valve Relaps

- GUCH – An Anesthesiological Perspective

- Thoracic Anesthesia for Lung Surgery

- Protamin

Cardiothoracic Anesthesia

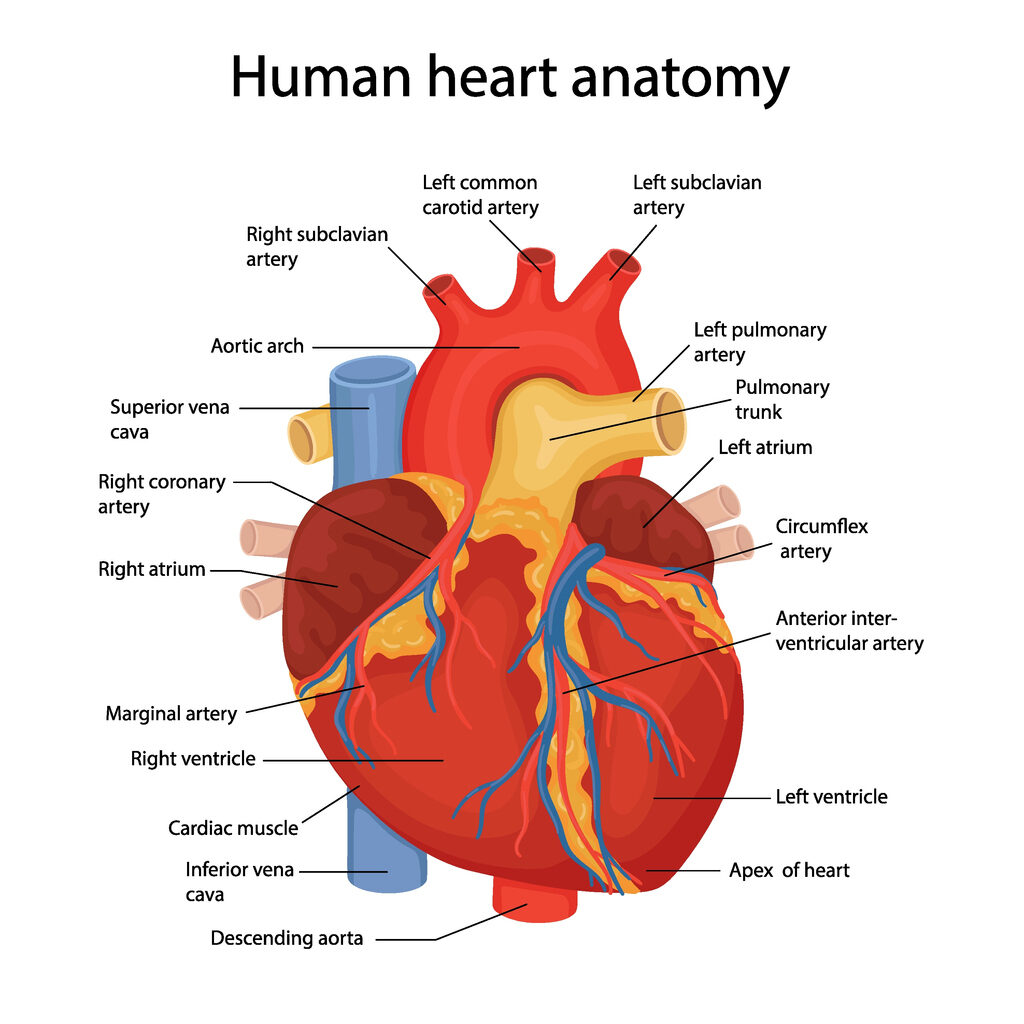

Cardiac Chambers and Valves

Aortic Valve

- Pressure: 120/70 mmHg

- Valve area: 2.5–3.5 cm²

Mitral Valve

- Valve area: 4–6 cm²

Pulmonic Valve

- Pressure: 25/10 mmHg

- Valve area: 2 cm²

Right Atrium

- Chamber pressure: 1–5 mmHg

- Chamber thickness: 2 mm

Left Atrium

- Chamber pressure: 3–12 mmHg

- Chamber thickness: 3 mm

Tricuspid Valve

- Valve area: 7–9 cm²

Right Ventricle

- Chamber pressure: 25/5 mmHg

- Chamber thickness: 4–5 mm

Left Ventricle

- Chamber pressure: 120/12 mmHg

- Chamber thickness: 8–15 mm

Anesthesia for Aortic Stenosis

- Avoid tachycardia – aim for 60-80 beats/min

- Maintain sinus rhythm

- Maintain preload

- Avoid hypotension – maintain SV

Aortic Valve

- Pressure: 120/70 mmHg

- Valve area: 2.5–3.5 cm²

Hemodynamics

- Fixed obstruction

- ↓ LV compliance

- ↑ PCWP

- ↔ / ↓ Cardiac output

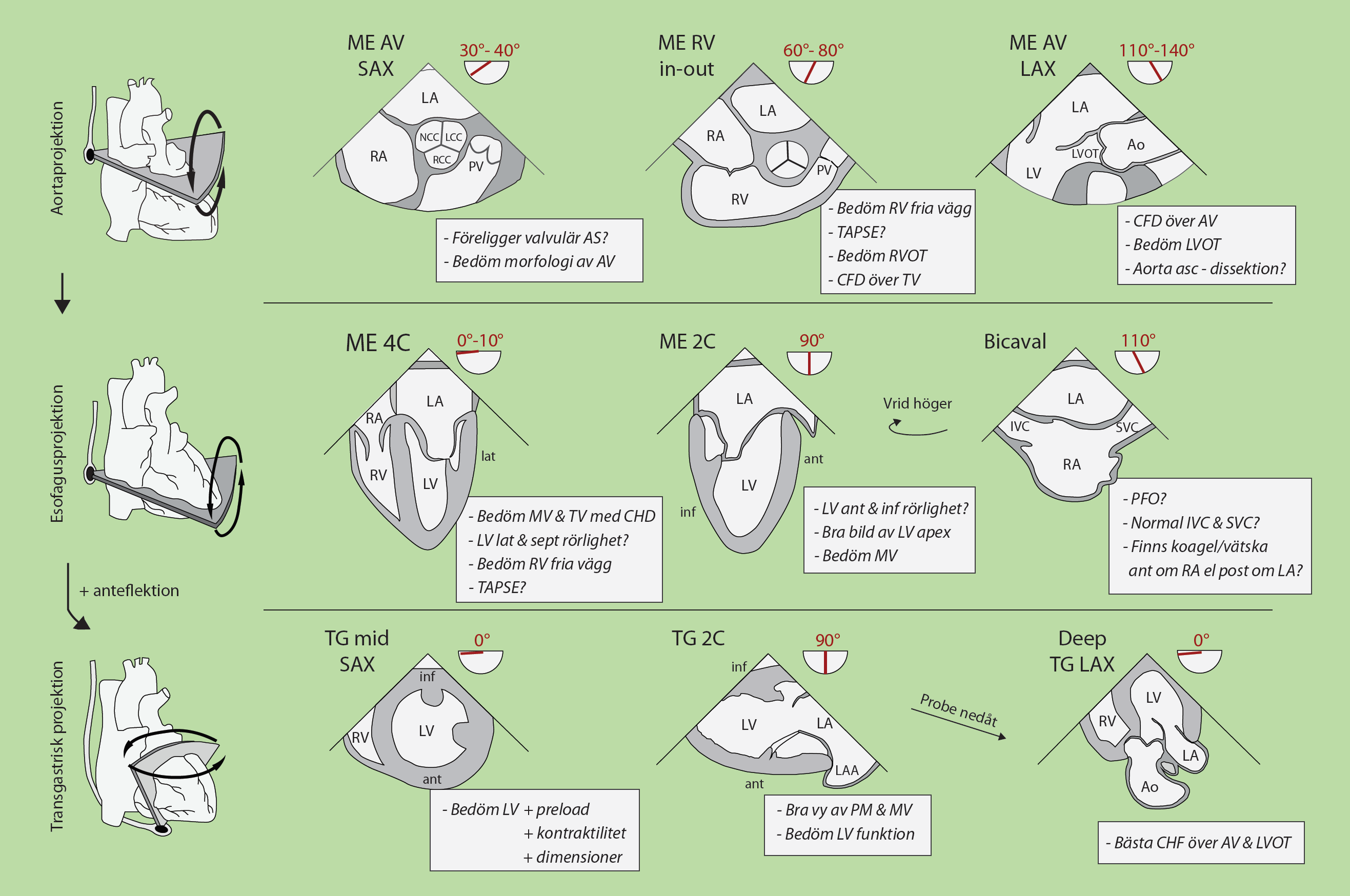

Echocardiography

- ↓ AVA

- ↓ DI

- ↑ AV gradient

- ↑ AT & AT/ET

- ↔ / ↓ LV EF (due to afterload mismatch)

Medical Management

- ↓ Ao-LV gradient

- ✔ Vasodilators

- ↓ LVEDP

- ⚠️ Diuretics

Mechanical Support Device

- ✔ IABP

- ✖ Impella

- ⚠️ VA-ECMO

- ↑ Risk of AV/LV thrombus

Anesthesia for Aortic Regurgitation

- Filled – Fast – Forward

- High -> normal heart rate (90/min) – possible beta agonist

- Maintain preload

- Low SVR – anesthesia

Aortic Valve

- Pressure: 120/70 mmHg

- Valve area: 2.5–3.5 cm²

Hemodynamics

- ↑↑ LV wall stress

- ↓ Coronary perfusion

- ↑↑ PCWP

- ↑ PAP

- ↓ Cardiac output

Echocardiography

- ↓ PHT (acute)

- Aortic flow reversal

- Early MV closure

- Diastolic MR

- ↓ LVEF (severe)

Medical Management

- ↓ Diastolic filling time

- ✔ TVP

- ✖ AV nodal blockers

- ↓ Regurgitant flow

- ✔ Vasodilators

- ↓ LVEDP

- ✔ Diuretics

Mechanical Support Device

- ✖ IABP

- ✖ Impella

- ⚠️ LAVA-ECMO

Anesthesia for Mitral Stenosis

- Similar to AS but with even more caution.

- Avoid tachycardia and hypotension!

- Beware of hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis (worsens pH)

Mitral Valve

- Valve area: 4–6 cm²

Hemodynamics

- ↑↑ LA pressure

- ↓ LVEDP

- ↑↑ PAP

- ↓↓ Cardiac output (RV failure)

Echocardiography

- ↑ MV gradient (varies with HR & BP)

- ↑↑ LA size

- ↑↑ RVSP

- ↑ IVS R → L

- (due to underfilled LV and RV failure)

Medical Management

- ↑ Diastolic filling

- ✔ Beta blockers (if CO preserved)

- ↓ Pulmonary edema

- ✔ Diuretics

- Maintain NSR

Mechanical Support Device

- ✖ IABP

- ✖ Impella

- ✔ LAVA-ECMO

- (LA drain to prevent pulmonary edema)

Anesthesia for Mitral Regurgitation

- Think AI -> high heart rate + adequate preload

- Low SVR – anesthesia, milrinone, nitropress, IABP

- Low PVR (beware of hypoxia, hypercapnia, and acidosis)

Mitral Valve

- Valve area: 4–6 cm²

Hemodynamics

- ↑↑ LA pressure

- ↑↑ PCWP

- ↑ V-waves

- ↓↓ Cardiac output

Echocardiography

- ↓ Jet velocity (LV-LA systolic gradient)

- ↑ E-wave velocity

- ↔ / ↓ LV EF

Medical Management

- ↓ Pulmonary edema

- ↑ LV stroke volume

- ✔ Vasodilators

- ✔ Diuretics

Mechanical Support Device

- ✔ IABP

- ✔ Impella

- ✔ VA-ECMO + LV vent

Tricuspid Regurgitation

Tricuspid Valve

- Valve area: 7–9 cm²

Hemodynamics

- ↔ PCWP

- ↔ / ↓ PAP

- ↑↑ RAP

- (“ventricularized” RA tracing)

- ↔ Cardiac output

Echocardiography

- Hepatic flow reversal

- Dense, triangular CW profile

- (rapid equalization of pressures)

- Plethoric IVC

Medical Management

- ✔ Diuretics

- ✔ Inotropes (if RV failure)

Mechanical Support Device

- ⚠️ RVAD

- ✔ VA-ECMO

Cardiac Tamponade

Clinical Picture

- Hypotension

- Elevated CVP

- Cold periphery

- Muffled heart sounds

- Tachycardia

- Reduced SvO2

- Jugular venous distension

- Pulsus paradoxus

Risk Factors

- Coagulation disorders

- Platelet inhibition

- Valve surgery

Echocardiography

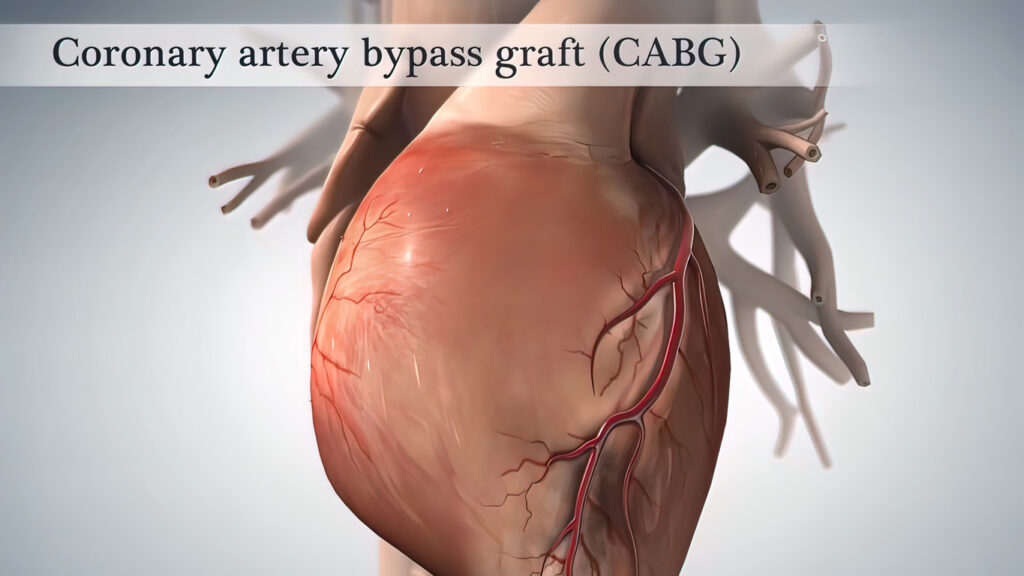

Anesthesia for Coronary Surgery

Coronary surgery (CABG) has been routinely performed in Sweden with great success since the early 1970s for the treatment of ischemic heart disease. In 2017, 2534 CABG surgeries were performed at 8 different hospitals. About 70% of patients are pain-free after 5 years, and about 50% are pain-free after 10 years. The average age is 66 years, and 75% are men. Less than 10% of patients undergo repeat surgery due to recurrence, but some are treated with additional PCI. The overall risk of serious complications for isolated coronary surgery is 4.3%, with a 30-day mortality rate of 1.1%, dialysis requirement in 1.1%, stroke in 0.6%, sternal infection in 0.6%, and 4% reoperation for bleeding. (ref: Swedeheart.se).

Patients with coronary artery disease are usually treated with either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery (CABG), depending on the extent and anatomy of the coronary artery disease.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association of Cardiac Surgery (EACTS) have divided the indications based on prognosis and symptoms according to the tables below.

Guidelines for Revascularization in Stable Coronary Artery Disease

(based on anatomical/functional extent of disease, prognosis, and symptoms)

Indications for Revascularization – Prognostic Benefit

Revascularization is recommended (Class I) in the presence of the following anatomical and/or functional findings:

- Left main coronary artery disease with stenosis >50% (Level of Evidence A).

- Proximal LAD stenosis >50% (Level of Evidence A).

- Two- or three-vessel disease with stenoses >50% in combination with impaired left ventricular function (LVEF <40%) (Level of Evidence A).

- Extensive ischemia, defined as >10% of the left ventricle (Level of Evidence B).

- Only one remaining patent coronary artery with stenosis >50% (Level of Evidence C).

Indications for Revascularization – Symptom Relief

Revascularization is recommended (Class I, Level of Evidence A) in:

- Coronary artery stenosis >50% in the presence of limiting angina pectoris or angina-equivalent symptoms despite optimal medical therapy.

Choice of Revascularization Method (CABG vs PCI)

The choice of method is based on disease extent, involvement of the proximal LAD or left main coronary artery, and the SYNTAX score.

One- and Two-Vessel Disease

One- or two-vessel disease without proximal LAD stenosis:

- PCI is recommended (Class I, Level of Evidence C).

- CABG may be considered (Class IIb, Level of Evidence C).

Single-vessel disease with proximal LAD stenosis:

- CABG and PCI are equivalent options (Class I, Level of Evidence A).

Two-vessel disease with proximal LAD stenosis:

- CABG is recommended (Class I, Level of Evidence B).

- PCI may be considered (Class I, Level of Evidence C).

Left Main Coronary Artery Disease

SYNTAX score ≤22:

- CABG and PCI are recommended (Class I, Level of Evidence B).

SYNTAX score 23–32:

- CABG is recommended (Class I, Level of Evidence B).

- PCI may be considered (Class IIa, Level of Evidence B).

SYNTAX score >32:

- CABG is recommended (Class I, Level of Evidence B).

- PCI is not recommended (Class III, Level of Evidence B).

Three-Vessel Disease

SYNTAX score ≤22:

- CABG and PCI are recommended

(CABG: Class I, Level of Evidence A; PCI: Class I, Level of Evidence B).

SYNTAX score 23–32:

- CABG is recommended (Class I, Level of Evidence A).

- PCI is not recommended (Class III, Level of Evidence B).

SYNTAX score >32:

- CABG is recommended (Class I, Level of Evidence A).

- PCI is not recommended (Class III, Level of Evidence B).

Summary Principle

CABG is the preferred first-line treatment in complex coronary artery disease, particularly in cases with high SYNTAX scores, left main coronary artery disease, and three-vessel disease. PCI is an equivalent alternative in less complex anatomy and low SYNTAX scores. Decisions should be made within a multidisciplinary heart team, taking into account clinical factors, comorbidities, and patient preferences.

Thoracic Surgery and Thoracic Anesthesia

Thoracic surgery mainly includes

- Coronary bypass surgery (CABG)

- Valve surgery (primarily aortic and mitral valve surgery)

- Combination of coronary artery surgery and concurrent valve surgery

- Thoracic aortic aneurysms and aortic dissections

- Arrhythmia surgery

- Correction of congenital heart defects

- Heart and lung transplants

- Various types of lung resections

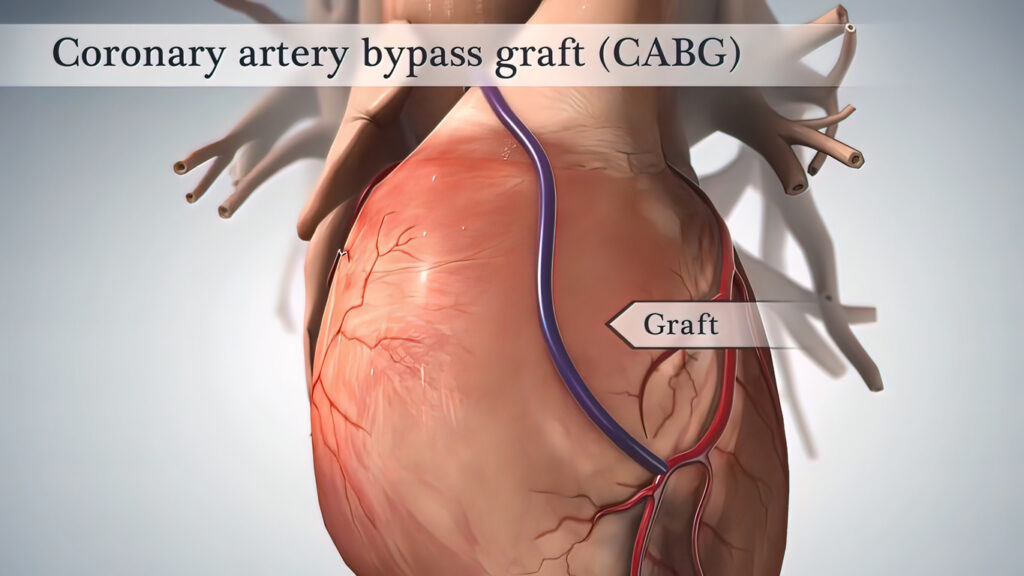

Coronary bypass surgery – CABG accounts for approximately 50% of all heart surgeries. Indications for CABG are stable angina, unstable angina, ongoing heart attack, or if the patient has had NSTEMI or previous STEMI with extensive coronary artery disease. The goal is symptom relief and/or increased life expectancy.

Anesthesia for Coronary Surgery

Coronary surgery is performed by surgeons specializing in thoracic surgery, and anesthesia is managed by specialists in thoracic anesthesia. Coronary surgery is usually performed on a still heart using a heart-lung machine after cardioplegia. The operation can be divided into three phases: a pre-machine phase, a phase on the heart-lung machine, and a post-machine phase when the patient regains their own circulation and respiration.

The operation typically begins with a sternotomy, where the chest is opened and the heart is cannulated by the surgeon. A cannula is placed in the aorta and one in the right atrium. Blood is drained (led out) from the patient’s veins or right atrium and collected in a venous reservoir. From the reservoir, blood is pumped through the heat exchanger, where the blood is cooled or warmed depending on the desired effect. The blood is then pumped through an oxygenator for oxygenation and carbon dioxide removal. The oxygenated blood returns to the patient through the aortic cannula to the aorta. After blood is diverted to the heart-lung machine and circulation is artificial, the heart is stopped using cardioplegia. Cardioplegia is a potassium-containing, often cold solution administered into the coronary arteries when the aorta is clamped.

The heart-lung machine (ECC) replaces the heart’s function, transitioning from normal pulsatile flow to a steady laminar flow controlled by pumps in the heart-lung machine. The machine includes several components, such as an oxygenator, heat exchanger, venous reservoir, cardiotomy reservoir, hemofilter, and mechanical parts like pumps, venous clamps, and cannulas. Gas exchange takes place in the machine instead of the lungs, with blood oxygenated via an oxygenator and carbon dioxide removed. The heart-lung machine is managed intraoperatively by a perfusionist in collaboration with the surgeon and anesthesiologist. The venous reservoir acts as a buffer between variable venous return and relatively constant pump flow.

During the heart-lung machine phase, the ventilator can be turned off. Without the ventilator, the lungs may collapse and form atelectasis. Recruitment maneuvers may be needed when weaning off the machine to mobilize the atelectasis. Alternatively, ventilation may continue with small volumes and low pressures to prevent disturbing the operation.

Bypass surgery involves suturing vein grafts to bypass occluded or stenotic coronary vessels. Vein grafts are typically taken from the patient’s own great saphenous vein and sewn over existing anastomoses, often 3-4 grafts (ranging from 1-6). The left internal mammary artery (LIMA) can also be used for the left anterior descending artery (LAD) to achieve revascularization of the heart. The goal of surgery is complete revascularization, meaning all vessels with >50% stenosis and a diameter >1.5 mm should be grafted. Normal surgery time is 2 to 3.5 hours.

Thoracic anesthesia requires the anesthesiologist to be well-versed in central hemodynamics and familiar with the pathophysiology of the diseased heart. The thoracic anesthesiologist must also be adept at invasive techniques, such as central venous access and central hemodynamic monitoring during anesthesia induction. They must be knowledgeable about the principles of anesthesia with the heart-lung machine and cardioplegia, including how to “go on” and “wean off” the machine. The thoracic anesthesiologist should be proficient in perioperative cardiac ultrasound, often using a transesophageal probe.

Preoperative Assessment

The preoperative assessment should evaluate the patient’s cardiac status, general condition, and physiology ahead of the surgery. Preoperative stress can lead to a sympathetic-induced increase in blood pressure and tachycardia, raising oxygen consumption, which should be avoided in cases of unstable angina with good premedication. Preoperative consultations are routine, and premedication is given according to need and local protocols, such as benzodiazepines and/or an opioid (e.g., Oxycontin 10 mg + Oxazepam 10 mg). Heavy premedication once common in thoracic surgery, such as high-dose morphine-scopolamine, is now rare due to side effects like hallucinations, respiratory failure, and pronounced somnolence.

Beta-blockers that the patient regularly takes should be continued, often at half the dose on the day of surgery to avoid intraoperative hypotension and post-heart-lung machine (ECC) bradycardia. Regarding anticoagulants, ASA should be continued, but Ticagrelor and Clopidogrel should be discontinued three and five days before surgery, respectively (see recommendations under the Coagulation chapter).

Preparation in the Operating Room

The operating table setup is checked by the responsible anesthesiologist before anesthesia induction. ECG is applied with five leads (leads V5 and II provide the best ischemia and rhythm detection), pulse oximetry, possibly BIS for anesthesia depth monitoring, and invasive blood pressure measurement. An arterial line is typically placed in the radial artery. In cases of low EF, a femoral arterial line may be placed, as it provides a more central pressure measurement (more reliable), and the radial pressure can show lower readings directly after weaning off the heart-lung machine. Defibrillator pads are routinely placed only during reoperations.

After anesthesia induction, a triple-lumen central venous catheter (16/20 cm long) is usually inserted for venous access and central hemodynamic monitoring. Sympathetic blockade induced by anesthesia should be minimized during induction, as it can lead to hypotension due to decreased inotropy, vasodilation, reduced preload, and bradycardia, which may lower perfusion pressure across critical stenoses, potentially triggering a vicious cycle of ischemia. Therefore, the patient’s sensitivity to hypotension should be assessed by noting changes in cardiac function, such as cardiac hypertrophy, reduced EF, regional wall motion abnormalities, and the extent of coronary artery disease and any main stem stenosis (e.g., EF 40%, triple-vessel disease, left main stenosis).

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE probe) is always used to detect cardiac function and regional wall motion abnormalities. Be sure to check for swallowing dysfunction, as TEE is contraindicated in cases of esophageal stricture, as the TEE probe could cause damage.

A pulmonary artery catheter (PA catheter/Swan-Ganz catheter) is not typically used in standard coronary artery surgery but may be useful in the intensive care unit afterward, particularly in cases of severe heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. Cardiac output measurement using pulse wave analysis is not appropriate intraoperatively due to the large changes in afterload and vasopressor use, which are known sources of error for the method.

Induction and Maintenance

Several drugs are used for anesthesia induction, varying by local routines and personal preference, but the principle is to maintain cardiac function and coronary perfusion pressure. Opioids are generally administered in high doses to avoid sympathetic stimulation, reducing the need for sedatives that are vasodilating and negatively inotropic (cardiodepressants). Common drugs in standard induction may include fentanyl 500-800 µg, propofol 60-100 mg, and rocuronium 40 mg, with anesthesia maintained using anesthetic gas, typically sevoflurane or isoflurane. In cases of lower ejection fraction or cardiogenic shock, higher doses of fentanyl and lower doses of propofol are given during induction. Alternatively, ketamine (Ketalar) 50-100 mg, midazolam, propofol, rocuronium, and fentanyl may be administered gradually. Anesthesia induction must be individualized based on the patient’s condition and heart function.

Intraoperative blood pressure control is managed primarily with vasopressor treatment, typically norepinephrine in boluses or infusion (0.05-0.5 µg/kg/min), or phenylephrine (0.1 mg). If bradycardia is present, ephedrine (5 mg) or epinephrine (0.01-0.1 mg) may be given.

Blood pressure increases are managed by increasing the anesthetic gas concentration, administering opioid boluses, or, if necessary, using nitroprusside infusion.

The anesthesiologist should balance and stabilize hemodynamics intraoperatively while also managing coagulation. Fibrinolysis inhibition with tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) can be administered to prevent bleeding (e.g., 2 grams at induction and 2 grams at protamine administration). Prophylactic antibiotics are routinely given, such as cloxacillin 2 g x 3, clindamycin 600 mg x 3, or cefotaxime 2 g x 3.

When administering anesthesia for cardiac surgery, one must account for the physiological changes that occur with oxygen deprivation in the heart and dramatic changes in heart rate and blood pressure. After a heart attack, ejection fraction (EF) and stroke volume (SV) are often reduced, sometimes significantly. During ongoing coronary ischemia, “hibernation” or “stunning” of the myocardium can temporarily reduce EF and SV, which may improve with revascularization. Myocardial oxygen delivery (DO2) depends on the degree and extent of coronary artery stenoses and coronary perfusion pressure. In cases of occlusion in one vessel area with concurrent stenosis in the collateral-supplying vessel, vasodilation can cause a “steal phenomenon,” redirecting blood flow from ischemic to already perfused (“luxury perfused”) areas. This can lead to ischemia, ST changes, and decreased heart motion.

Myocardial oxygen consumption increases with increasing heart rate and wall tension. Long-term hypertension can lead to left ventricular hypertrophy, impairing myocardial oxygenation. Reducing afterload and preload, as well as slowing the heart rate, can alleviate ongoing oxygen deprivation. In cases of critical coronary artery stenosis, coronary perfusion pressure is crucial for maintaining flow, as post-stenotic vessels are dilated and flow becomes pressure-dependent.

During cardiac anesthesia, it is essential to optimize oxygen content and oxygen delivery with good hemoglobin levels and oxygen saturation, maintain sufficient but not excessive perfusion pressure, and achieve an appropriate heart rate. Intraoperatively, a heart rate of 70-100 beats per minute and a mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 70-90 mm Hg are generally desirable. Optimal physiology may vary for different heart valve diseases or other cardiac abnormalities.

Maintenance Anesthesia

Inhalation anesthesia has been shown in several studies to result in lower levels of cardiac damage markers and is generally considered to have a cardioprotective effect, with a reduced risk of mortality and complications compared to TIVA (Uligh et al. Anesthesiology 2016). The EACTS guidelines from 2017 recommend the routine use of inhalation anesthetics for cardiac surgery. A MAC value of 0.8-1.5 is usually used intraoperatively. Adjustments of anesthetic gases can also be used to regulate blood pressure intraoperatively.

Extracorporeal Circulation

For heart-lung machine (ECC) use, the heart is cannulated on the venous side in the right atrial appendage down into the inferior vena cava and on the arterial side in the ascending aorta. Beforehand, heparin 350 E/kg is given intravenously as a bolus dose to achieve an ACT value over 470 seconds. Heparin is administered intravenously (in a line where ACT sampling is not taken to avoid false high values). If heparin’s effect is insufficient, antithrombin III may need to be substituted.

With a heart-lung machine, the body’s circulatory physiology fundamentally changes. During ECC, all circulation in the lungs decreases or ceases, and inhalation agents can no longer be supplied to the bloodstream via the anesthesia machine. However, the heart-lung machine’s oxygenator can allow anesthetic gas through, and it is possible to connect a vaporizer to the heart-lung machine to continue gas anesthesia if desired. Alternatively, total intravenous anesthesia (e.g., propofol infusion) can be administered during ECC. Anesthesia depth can be monitored using BIS.

Cardioplegia, either cold crystalloid or warm blood cardioplegia, is administered by the thoracic surgeon into the coronary arteries to stop the heart after cannulation, and it is repeated approximately every twenty minutes during surgery with a stopped heart.

The target intraoperative blood pressure during ECC is debated. Lower pressure in the presence of critical stenosis, both known and unknown, can result in blood pressure-dependent flow and the risk of ischemia. A MAP about 30 mm Hg below preoperative baseline increases the risk of kidney failure (Kanji et al. JCTS 2010). The risk of stroke is increased with both low or high blood pressure (Vedel et al. Circulation 2018). The heart-lung machine flow is usually set at 2.4 L/min/m2 and provides oxygen delivery independent of blood pressure but dependent on hematocrit. An oxygen delivery below 270 ml/min/m2 has been associated with a higher risk of kidney injury. Since the heart-lung machine’s priming solution is about 1300 ml, dilution of the total blood volume occurs, which can result in a critically low hematocrit. Hematocrit reduction can be countered by reducing the priming volume or transfusing blood.

During weaning from the heart-lung machine (ECC weaning), ventilation is first restarted after possible lung recruitment. The venous line to the heart-lung machine is gradually clamped so that venous return goes back to the right ventricle instead of into the heart-lung machine. The heart gradually fills, increasing stroke volumes until the intracardiac pressure exceeds aortic pressure, pumping blood out through the aortic valve, restoring a pulsatile arterial waveform. The heart begins beating again. Often, the heart starts in sinus rhythm, but sometimes ventricular fibrillation occurs, requiring defibrillation with internal paddles or administration of approximately 10-20 mmol of potassium chloride, which induces transient asystole, often followed by sinus rhythm.

As the blood reservoir fills less, and when the heart is filled and the MAP is acceptable between 50 and 70 mm Hg, ECC is gradually reduced, while monitoring that the heart’s filling and MAP remain stable. Heart motion and potential valve insufficiencies are observed. Increasing filling pressure and decreasing arterial pressure indicate heart failure, which may require inotropic drugs, such as calcium gluconate (100 mg/ml 10 ml), ephedrine 5 mg, or milrinone 2-3 mg. Alternatively, ECC can be ramped up again, and after additional reperfusion time, a new weaning attempt is made. During the reperfusion period, heart muscle “stunning” tends to decrease.

If ECC weaning is not immediately successful, the bypass graft flows should be checked with a flow meter, and ultrasound assessment of regional wall motion defects corresponding to the grafted areas should be performed. It may be necessary to re-suture an anastomosis or graft distally. If flow is good and failure persists, initiate inotropic infusion (e.g., milrinone 0.5 µg/kg/min, dopamine 2.5 µg/kg/min, or levosimendan). Consider an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), which both offloads the heart and improves coronary perfusion pressure in severe heart failure. Heparin is neutralized with Protamine 0.7-1 mg/100U heparin, and ACT measurement should be <130 seconds, or below baseline if measured before surgery.

Postoperative Care after Cardiac Surgery

After surgery, the patient usually has 2 drainage tubes in the chest, one mediastinal and one in the left pleura if it has been opened (often opened during LIMA harvesting). Acceptable initial drainage loss is 100-200 ml during the first hour but should decrease thereafter. If bleeding increases, coagulation factors should be substituted based on coagulation tests, such as thromboelastography-TEG. Additional protamine, plasma, fibrinogen, or platelets may need to be administered. Extubation is performed according to local criteria, but body temperature should be >36 degrees, there should be no imminent reoperation due to increasing bleeding, and FiO2 should be <40% with PEEP of 5-10 cm H2O. Shivering is treated with a warming blanket and possibly an opioid (e.g., Pethidine 10-20 mg iv).

Pain relief regimens should include paracetamol and opioids, e.g., paracetamol 1 g x 4, Oxycontin 5-10 mg x 2, Oxynorm 5 mg as needed. NSAIDs should be avoided, especially in those at risk of kidney failure, but can be tried in patients with preserved kidney function (e.g., Toradol 15-30 mg as needed).

PCA pumps with morphine can be used.

Antibiotic prophylaxis should be given routinely for 1-2 days (e.g., cloxacillin 2 g x 3, clindamycin 600 mg x 3, or cefotaxime2 g x 3).

TEDA – Thoracic Epidural Anesthesia

Thoracic epidural anesthesia has been used for intraoperative pain relief and sympathetic block. However, there is a risk of epidural bleeding as this patient group is older, generally vascularly diseased, often on antiplatelet therapy, and fully heparinized intraoperatively. Pain relief for heart surgery with TEDA is comparable to that with PCA. If anesthesia is used, it should be administered well in advance of heparinization. Aim for a block from Th 2-10 for sympathetic block, which provides protection against tachycardia and vasodilation.

Anesthesia for the Cardiac Patient

The chapter can be divided into

- Coronary artery disease (CAD)

- Heart failure (systolic, diastolic)

- Pulmonary hypertension, right ventricular failure

- Aortic valve disease

- Mitral valve disease

Surgical stress increases myocardial oxygen demand

- Increased heart rate

- Increased wall tension (P x r/w)

- Increased blood pressure (P)

- Increased radius (r) (due to increased LVEDFP)

- Increased contractility

- Increased sympathetic activity

- Increased circulating catecholamines

Disruption of the myocardium’s supply/demand ratio for O2 during surgery in patients with coronary artery disease

Increased “demand” – increased need

- Tachycardia

- Increased wall tension

- LV radius

- Arterial pressure

- Increased contractility

Decreased “O2-supply” – decreased delivery

- Tachycardia

- Hypotension

- Decreased O2 content

- Thrombosis (hypercoagulation, plaque rupture)

- Vasoconstriction

Cardiac Sympathetic System and CAD

Efferent pathways (Th1-Th5)

- Beta receptors mediate:

- Heart rate

- Contractility

- Increased MVO2 causes metabolic vasodilation

- Alpha receptors:

- Epicardial coronary arteries: stimulation causes vasoconstriction

- Coronary resistance vessels: stimulation causes vasoconstriction

Increased sympathetic activity to the heart during stress in coronary artery disease patients

- Increased MVO2

- Constriction of stenotic coronary arteries

- Plaque rupture – thrombosis

- Catecholamines increase platelet aggregability

- Decreased arrhythmia threshold

Anesthesia and Coronary Artery Disease (CAD)

- Assessment of surgical risk (degree of surgical stress, duration, emergency/elective)

- Identify high-risk patients

- Preoperative investigation and treatment

- Perioperative treatment/prophylaxis

- Choice of anesthesia technique

Preoperative Risk Factors for Cardiac Complications (Revised Cardiac Risk Index)

- Age > 75 years

- Heart failure

- Ischemic heart disease

- Cerebrovascular disease

- Diabetes

- Kidney failure

- 0 risk factors = low risk

- 1-2 risk factors = intermediate risk

- ≥ 3 risk factors = high risk

Preoperative Investigation for High-Risk Surgery

- If 1-2 risk factors, no preoperative investigation

- If ≥ 3 risk factors, non-invasive stress testing is recommended

Non-Invasive Stress Test

- If negative – no specific action required

- If positive, coronary angiography is recommended

- If positive, coronary revascularization is recommended

Revascularized Patients Before Elective Surgery – “Timing”

- Delay elective surgery for at least 6 weeks, preferably 3 months after PCI with stent

- Delay elective surgery 12 months after PCI with drug-eluting stent (DES)

- If CABG was performed within five years, no investigation is necessary

Coronary Syndrome – Unstable CAD

- Rapid revascularization is prioritized before elective surgery

- In acute surgical disease and concomitant unstable CAD, surgery is prioritized

- Balloon dilation without stent before urgent surgery?

Perioperative Myocardial Infarction (PMI)

- Patients with or at risk for atherosclerosis (n=8351)

- Devereaux Ann Internal Med 2011;154:523

- Criteria for PMI:

- PAD or

- Troponin/CK-MB elevation and any of the following:

- Ischemic symptoms, Q wave, ischemic

- ECG changes, coronary intervention

- 5% PMI ≤ 30 days

- 75% of these ≤ 2 days

- 2/3 have no clinical symptoms

- 30-day mortality 11.6% vs. 2.2%

Perioperative Beta-Blockade and CAD

Effects of Extended-Release Metoprolol Succinate in Patients Undergoing Non-Cardiac Surgery

POISE trial: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2008;31:1839-1847

- 8351 patients with or at risk of atherosclerosis undergoing general surgery were randomized to

- Placebo (n=4177)

- Extended-release metoprolol (n=4174)

- Dosage: 100 mg 2-4 h preop. + 100 mg < 6 h postop. 12 h after the 1st dose, 200 mg daily for 30 days

- If oral administration is not possible, 15 mg x 4 iv

- SAP > 100 and HR > 50/min before dosing

- Primary endpoint: cardiovascular death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, or cardiac arrest

Recommendations (Class I) for Perioperative Beta-Blockade

- ACC/AHA

- Continue beta-blockade peri- and postoperatively in patients who are preoperatively treated with beta-blockers

- ESC/ESA

- Known coronary disease

- High-risk surgery

- Continue beta-blockade peri- and postoperatively in patients who are preoperatively treated with beta-blockers

- When to start beta-blockade? – a month or at least a week before surgery, dose titration required

- Therapeutic goal for heart rate?: 60-70/min

- How long to continue beta-blockade? – a month

Recommendation

- Non-invasively investigate patients with ≥ 3 risk factors (stress ECG, stress echo)

- If pathological, coronary angiography

- If significant coronary disease, revascularization before major general surgery

- Preoperative treatment with beta-blockers, continue perioperative beta-blockade

- Perioperative beta-blockade: patients undergoing high-risk surgery, patients with known CAD, high-risk patients (≥ 3 risk factors)

- Avoid hypotension and bradycardia!

- If contraindications to beta-blockade, consider clonidine

Other Heart Medications Before Surgery for CAD

- Statins – start one month before surgery

- Nitrates – no protective effect

- ACE inhibitors – continue therapy postoperatively in patients with heart failure. Note risk of hypotension!

- Calcium channel blockers – only for patients with Prinzmetal’s angina

- ASA (?)

Study: “Aspirin in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery”

Devereaux NEJM 2014;370:1494

- Non-aspirin treated (n=5628)

- Placebo

- Aspirin, 200 mg pre-op, 100 mg/day for 30 days

- Ongoing aspirin treatment (n=4382)

- Placebo

- Aspirin, 200 mg pre-op, 100 mg/day for 7 days

- Primary endpoint: death or non-fatal infarction after 30 days

Premedication for CAD

- Benzodiazepines (diazepam 0.1-0.15 mg/kg)

- Morphine 0.1 mg/kg

- Scopolamine 0.2-0.4 mg

Monitoring for CAD and High-Risk Surgery

- Invasive blood pressure

- 2-3 lead ECG, ST trend

- CVP

- PA catheter – not indicated

- TEE – for intraoperative ischemia or pronounced hemodynamic instability

Anesthesia Induction and CAD

- Hypnotics:

- Midazolam

- Ketamine

- Propofol

- Opioids (fentanyl)

- Inhalation agents (sevoflurane, desflurane)

Maintenance of Anesthesia for CAD

- Sevoflurane

- Desflurane

- TIVA (opioid + propofol)

Inhalational Anesthetics, Central and Coronary Hemodynamics

- Inhalation agents have a negative inotropic effect

- Inhalation agents are vasodilatory (lower SVR), open ATP-dependent K+ channels

Inhalation Agents are Coronary Vasodilators

Isoflurane and Lactate Production in Patients with CAD

Published studies with Coronary Steal

| Study author | Year | Number of patients | Total patients with lactate production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reiz | 1983 | (n=21)* | 1 |

| Reiz Östman | 1985 | (n=13)* | 1 |

| Moffit | 1986 | (n=10) | 3 |

| Larsen | 1986 | (n=10) | 4 |

| O´Young | 1987 | (n=7) | 0 |

| Khambatta | 1988 | (n=10)* | 4 |

| Sahlman | 1989 | (n=21) | 2 |

| Pulley | 1991 | (n=20) | 3 |

| Diana | 1993 | (n=18) | 3 |

| Hohner | 1994 | (n=20) | 1 |

| Total: | 150 | 22 (14,7%) |

Sevoflurane and Coronary Artery Disease?

Do Inhalation Agents Have Cardioprotective Effects?

Mechanisms Behind the Cardioprotective Effects of Inhalation Agents

- Anti-ischemic effect

- Preconditioning effect

- Postconditioning effect (reduces reperfusion injury after ischemia)

”Randomized Comparison of Sevoflurane Versus Propofol to Reduce Perioperative Myocardial Ischemia in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery”. Lurati Buse et al Circulation 2012;126:2696

- Patients with known CAD or ≥ 2 risk factors for CAD and major surgery

- Randomized to

- Propofol (n=201)

- Sevoflurane (n=184)

Primary endpoint: myocardial ischemia (continuous ECG, troponin)

Cardioprotective Effect of Regional Anesthesia for CAD?

Liu et al. Anesthesiology 1995;82:1474-1506

Can Perioperative EDA Provide a Cardioprotective Effect?

Lumbar Epidural Anesthesia (LEA) Versus Thoracic Epidural Anesthesia (TEA)

Lumbar Epidural Anesthesia (LEA) vs Thoracic Epidural Anesthesia (TEDA)

- Lumbar epidural anesthesia? No!

- Thoracic epidural anesthesia? Yes! (Evidence Class IIa, Level A)

- If administered peri- and postoperatively!!!

Perioperative Management of Heart Failure

Chronic Heart Failure

- Prevalence ≈ 2%

- > 75 years, prevalence ≈ 8%

- In the next 10-20 years, prevalence will increase 2-3 times

- Increased age

- Today, more patients survive acute infarction but develop heart failure

Chronic Heart Failure – Clinical Syndrome

- Reduced ventricular function

- Increased pulmonary pressure

- Reduced physical capacity

- Neuroendocrine activation

- Decreased survival

Pharmacological Treatment

- ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin-II receptor blockers

- Beta blockers (metoprolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol)

- Aldosterone receptor antagonists

- Diuretics

- Digoxin

Pharmacological Treatment

- ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin-II receptor blockers

- Beta blockers (metoprolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol)

- Aldosterone receptor antagonists

- Diuretics

- Digoxin

ACE Inhibitors, Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers

- Decrease angiotensin II, catecholamines, aldosterone

- ADH. Increase bradykinin, NO, PGI2

- Reduced production of tissue angiotensin II

- Antiproliferative effect, reduces remodeling

Beta Blockers (metoprolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol)

- Decrease MVO2, increase glucose uptake, improve energy utilization, antiarrhythmic effect, reduce Ca2+ leakage from SR, anti-apoptotic effect, antioxidant

Aldosterone Receptor Antagonists

- Reduce myocardial collagen, lower catecholamines, improve baroreflex, improve endothelial function (via NO)

Prognostic Value of Natriuretic Peptides

Brain Natriuretic Peptide (B-type Natriuretic Peptide, BNP)

- Produced in the left ventricle and released upon ventricular wall distension (increased preload)

- Released together with NT-proBNP, which is biologically inactive

- Vaso-venodilation, increases GFR, natriuresis, inhibits RAAS

Prognostic Value of Natriuretic Peptides (BNP, NT-proBNP)

- Pre-op elevation of BNP/NT-proBNP increases the risk of:

- MACE (infarction, cardiac death) (OR: 19.8)

- Mortality (OR: 9.3)

- Cardiac death (OR: 23.9)

- “Cut-off” level?

- Method

- BNP/NT-proBNP compared to other methods?

NT-proBNP, Thresholds

- < 400 ng/l heart failure unlikely

- 400-900 ng/l possible heart failure

- > 900 ng/l heart failure likely

Perioperative Management

- Identification of high-risk patients (EF, preoperative functional status, NT-proBNP, clinical presentation)

- Is the patient optimally treated for heart failure?

- What do we do with “heart failure medications” before surgery?

Pharmacological Treatment

- ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers

- Beta blockers (metoprolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol)

- Aldosterone receptor antagonists

- Diuretics

- Digoxin

Perioperative Management

- Identification of high-risk patients (EF, BNP, clinical)

- Is the patient optimally treated for heart failure?

- What do we do with the “heart failure medication” before surgery?

- Choice of anesthesia technique (regional, general anesthesia?)

Case report

- Pregnant, week 36

- 190/100 mmHg, 130/min

- Dyspnea

- Systolic murmur (MI?)

- Pulmonary edema

- Continuous spinal (Th 6) for 14 hours

- Regional anesthesia for surgery in the lower body in a patient with heart failure

Case report

- 37-year-old woman with twin pregnancy at 33 weeks. Seeks emergency care due to shortness of breath and leg swelling. Previously heart-healthy.

- BP: 110/60, HR: 120, SpO2 90%

- Slight increase in CK-MB. ECG: repolarization disturbance.

- Echo: biventricular failure. LVEF: 20% MI, TI grade 3/4

- Treatment started with furosemide and nitroglycerin infusion

- Decision for emergency C-section

- Anesthesia technique?

Anesthesia induction in heart failure

- Hypnotics:

- Midazolam

- Ketamine

- Propofol

- Opioids (fentanyl)

Hemodynamic effects of Anesthetics

| Anesthetic Agent | Negative inotropic effect | Vasodilatation | Filling pressure | Heart rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Propofol | yes | yes | reduces | varies |

| Fentanyl | no | yes | reduces | reduces |

| Ketamin | ? | no | increases | increases |

| Isoflurane | yes | yes | unchanged/increases | increases |

| Sevoflurane | yes | yes | unchanged/increases | increases |

| Midazolam | yes | yes | reduces | increases |

Maintenance of anesthesia

- TIVA (propofol, opioid)

- Inhalation anesthesia

Intraoperative monitoring in heart failure

- Invasive blood pressure

- 2-3 lead ECG, ST trend

- PA catheter (SvO2, CCO)

- Central venous catheter (ScVO2)

- TEE – for pronounced hemodynamic instability

Recommendations

- Identify high-risk patient

- Arterial line, central venous catheter (the day before)

- Arterial pressure (MAP), central venous oxygen saturation before induction

- Connect milrinone, norepinephrine (NA) to central venous catheter

- Anesthesia technique you’re familiar with

- Control MAP (65-75 mmHg) with NA

- Control central venous oxygen saturation (≈ 60-70%) with milrinone

- Control fluid administration with CVP

- Hemoglobin > 100 g/l

- Have two anesthesiologists at the start of anesthesia!

Diastolic heart failure

Diastole

- Myocardial relaxation

- Active, energy-demanding process

- Affected by ischemia and

- Inotropic drugs

- Passive filling

- Extracardiac factors

- Structural factors

Diastolic dysfunction

- Definition:

- Normal filling pressure results in insufficient LV filling

- Elevated filling pressure required for adequate LV filling

- 40-50% of heart failure patients have isolated

- Diastolic dysfunction

Isolated diastolic dysfunction

- LVEF is normal, LVEDV is low

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- Abnormal mitral Doppler (E/A <1)

- Hypertension, aortic stenosis

- Dynamic LV outflow obstruction (functional aortic stenosis)

Treatment of LV outflow obstruction with SAM

- Increase preload (“volume challenge”)

- Avoid tachycardia

- No inotropic drugs

- No vasodilators

- For tachycardia, give β-blockers

- Guide therapy with echo-Doppler !!!

Anesthesia in pulmonary hypertension

Pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure

Pulmonary circulation and the right ventricle

Interaction between RV and LV (“ventricular interdependence”)

- Changes in pressure/volume in one ventricle directly affect the other

- Immediate force transfer between RV and LV

- Shared muscle fibers, septum, pericardium

- Diastolic and systolic interaction

Diastolic ventricular interaction with pressure/volume overload of the RV

- Increased RV volume/distension during diastole, septum shifts leftward

- Reduces LV volume, i.e., reduced LV preload

- LV end-diastolic pressure (PCWP) increases

- LV compliance decreases

Systolic ventricular interaction with pressure/volume overload of the right ventricle

- With RV pressure/volume overload, a flattened septum shifts from left to right during systole

- LV assist is more effective at high systemic pressure

- RV function deteriorates at low systemic pressure (peripheral vasodilation)

Pulmonary hypertension

- MPAP > 25 mmHg or SPAP > 55 mmHg

- Right ventricular hypertrophy/failure

Classification

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- Primary, idiopathic pulmonary hypertension (sporadic, familial)

- Related to collagen vascular diseases (scleroderma, lupus, RA)

- Portopulmonary hypertension

- Pulmonary venous hypertension (LV failure, MI/MS, AS)

- Pulmonary hypertension associated with lung disease

- Pulmonary hypertension caused by thromboemboli

Anesthesiological aspects of pulmonary hypertension

Anesthesia in primary/secondary pulmonary hypertension and RV failure

- Continue chronic medication for pulmonary hypertension (Ca

2+ antagonists, sildenafil, ET antagonists, i.v. PGI2) - Switch i.v. PGI2 to inhalation

- Light premedication

- Insertion of PA catheter before induction (CVP, PA)

Anesthesia in primary/secondary pulmonary hypertension and RV failure

- TIVA (propofol/opioid)

- Avoid ketamine, N2O (increases PVR) and inhalation agents (negative inotropic effect)

- TEE for monitoring RV function

- Hypoxia and hypercapnia increase PVR

- Regional anesthesia: may cause undesirable blood pressure drop and RV failure

- Norepinephrine for high SVR (MAP)

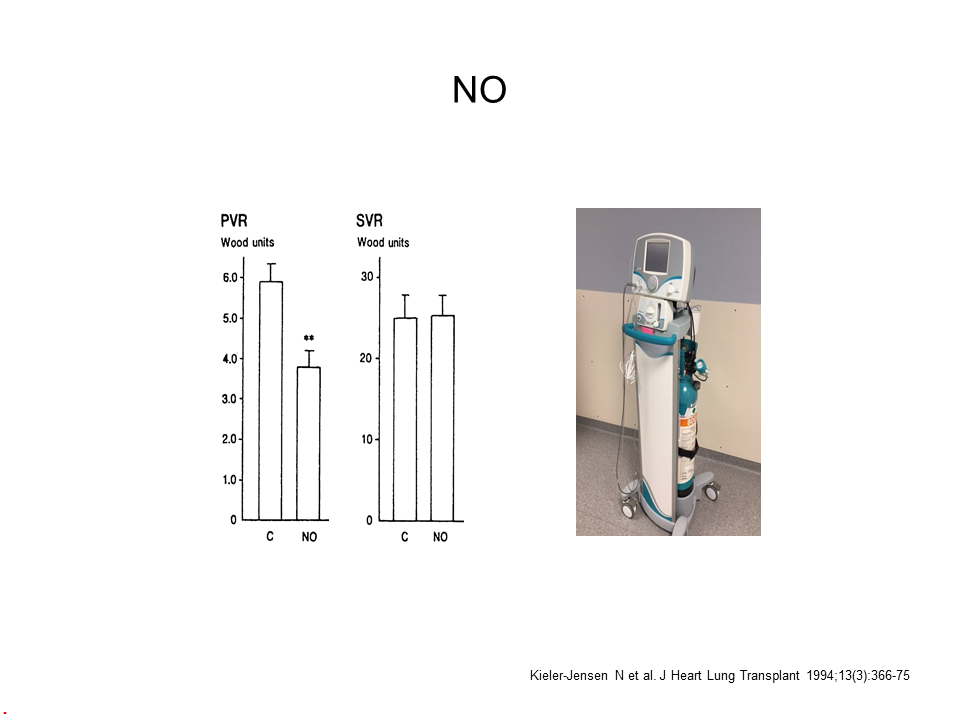

- Inhaled NO, prostacyclin, and/or milrinone (selective lowering of PVR)

- For RV failure, i.v. milrinone + norepinephrine

Prevention/treatment of pulmonary hypertension and RV failure

- Optimize RV preload (CVP 10-15 mmHg)

- High systemic pressure improves LV support and enhances RV perfusion

- Reduce pulmonary vascular resistance selectively (inhaled NO, milrinone, prostacyclin)

- Inotropic therapy for RV failure

Conclusions

- The prevalence of chronic heart failure is continuously increasing

- Understand the pathophysiology

- Identify high-risk patients

- Anesthesia technique itself is less important

- Adequate monitoring

- Use inotropic/vasoactive drugs as needed

- Do not forget the diagnosis of dynamic LV with outflow obstruction in the event of sudden, severe intraoperative cardiogenic shock

- Norepinephrine + inhalation of vasodilators for pulmonary hypertension and RV failure

Positive pressure ventilation in pulmonary hypertension and RV failure

- Hypoxia and hypercapnia increase PVR and RV afterload

- Increased respiratory rate increases intrinsic PEEP + “gas trapping”

Aortic stenosis

When is there an increased risk of giving anesthesia to patients with aortic stenosis?

Severe AS

- Valve area ≤ 1 cm2

- Mean gradient ≥ 50 mm Hg

Combined with

- Reduced LV systolic function (EF < 40%)

- Symptomatic AS (angina, syncope, dyspnea)

- Associated mitral relaps

- CAD (25-50%)

- High-risk surgery carries mortality between 2-10%

Pathophysiological aspects

- Compensatory LV hypertrophy (concentric) normalizes tension in LV afterload (P x r/2w)

- Impaired diastolic function

- Reduced ventricular compliance

- Impaired active relaxation

- Normal end-diastolic volume (stretching of sarcomeres) requires high filling pressure (PCWP)

- Intact atrial function is essential

Myocardial O2 “supply/demand mismatch” in aortic stenosis

O2 demand

- Increased LV mass

- Increased wall tension

- Heart rate

- Contractility

O2 supply

- High LVEDP

- Increased tissue pressure

- Reduced coronary perfusion pressure

- Decreased coronary vascular reserve

- Increased wall/lumen ratio

- Reduced capillary density (20-30%)

- CAD (25-50%)

Pathophysiological aspects

- Hypotension/tachycardia –> supply-demand mismatch –> ischemia –> decreased SV –> hypotension ischemia

- “Vicious cycle” with rapid progression to cardiogenic shock

Hemodynamic goals: Aortic stenosis

- Heart rate: 65-80

- Rhythm: Sinus

- Preload: High

- SVR: Normal/high

- Inotropy: Normal/reduced

Anesthesia and aortic stenosis in general surgery

- Identify patient. Murmur?

- No correlation between murmur intensity and severity of aortic stenosis

- Order echo-Doppler examination

- Always consider valve surgery before elective surgical procedures!!

- Increased perioperative risk with gradient > 50 mm Hg or area ≤ 1 cm2

Anesthesia and aortic stenosis in general surgery

- Avoid hypovolemia (give colloid)

- Avoid vasodilation (phenylephrine, norepinephrine)

- Maintain sinus rhythm

- Avoid inotropic support

- Be aware of the risk of myocardial ischemia!!

- Heavy premedication, relaxed patient (ß-blockade)

- High doses of fentanyl (5-10 µg/kg)

- Low doses of hypnotics (propofol: 1-1.5 mg/kg)

- TIVA, sevoflurane-fentanyl

- Avoid regional anesthesia (relative contraindication)

- Serum hemoglobin > 100 g/l

Monitoring

- Standard 3-lead ECG, pulse oximetry

- Arterial catheter

- PAC with CCO and continuous SvO2 in severe symptomatic AS and high-risk surgery

- Central venous catheter with CVP measurement and continuous ScvO2

- TEE: “Recommended if acute and severe hemodynamic instability develops perioperatively” (Class I)

Patient case

- Hypertension, hyperlipidemia

- Severe aortic stenosis (area = 0.8 cm2, gradient 70 mm Hg, EF = 60%)

- Coronary angiogram: significant two-vessel disease

- Anemia

- Workup shows circumscribed rectal cancer, risk of imminent ileus

Aortic insufficiency

Short film Bicuspid Valve

Short film aortic valve with regurgitation

Short film mitral relaps

Short film mitral relaps with color doppler

Pathophysiological aspects

- Volume overload of LV

- The degree of regurgitation is determined by:

- Aortic valve defect

- Aortoventricular pressure gradient

- Duration of diastole

- Chronic volume overload causes eccentric hypertrophy

- Reduced contractility

- High heart rate reduces regurgitation and increases “forward output”

- Lowered SVR reduces regurgitation and increases “forward output”

- Combine vasodilators (e.g., nitroprusside, nitroglycerin) with volume to avoid excessive lowering of preload

Hemodynamic goals in aortic insufficiency

“Faster, fuller, and vasodilated”

- Heart rate: 85-100

- Rhythm: Sinus

- Preload: High

- SVR: Low

- Inotropy: Normal

Anesthesia and aortic insufficiency in non-cardiac surgery

- Normal premedication and induction

- “Vasodilator anesthesia”

- Opioid + isoflurane

- Regional anesthesia

- Use PA catheter in heart failure symptoms/low EF

- For low CO/SVO2 use inodilators (milrinone, levosimendan)

Mitral Valve Stenosis

Pathophysiological aspects

- High atrioventricular pressure gradient for adequate LV filling

- Tachycardia increases gradient

- LA dilated, LV hypovolemic

- Pulmonary hypertension, high PVR

- Clinical symptoms when MVA < 2.5 cm2

- Severe MS: MVA < 1.0 cm2

- RV hypertrophy

- RV failure + tricuspid regurgitation

- Atrial fibrillation is common

- CAD is rare

Hemodynamic goals: Mitral stenosis

- Heart rate: 65-80 beats per minute

- Rhythm: Sinus

- Preload: Normal/high

- SVR: Normal/high

- Inotropy: Normal

Anesthesia and mitral stenosis in non-cardiac surgery

- Heavy premedication

- High-dose fentanyl

- Low-dose fentanyl + inhalation agents

- Phenylephrine/norepinephrine for hypotension

Anesthesia and mitral stenosis in non-cardiac surgery

- Avoid tachycardia! Use digitalis, ß-blockers

- Maintain sinus rhythm!

- TEE

- PA catheter, monitor both CVP and PCWP. Optimize intravascular volume

- High CVP leads to RV failure

- “Low PCWP” results in hypovolemic LV

- For RV failure, inodilators + inhaled NO or prostacyclin

Conclusion

- Pathophysiology of heart diseases

- Identify high-risk patients

- Effects of anesthetics/techniques on the cardiovascular system

- Monitoring

- Vasoactive drugs

Minimize perioperative morbidity!

Mitral Valve Relaps

Common causes of mitral regurgitation

- Prevalence 1-2%

- Organic (primary)

- Myxomatous degeneration

- Fibroelastic “deficiency”

- Calcification

- Functional (secondary), CAD

- LV failure (remodeling)

- Rupture of papillary muscle

Mitral Valve relaps

Mitral Valve relaps

When is there an increased risk of giving anesthesia to patients with mitral regurgitation?

Bajaj et al. Am J Medicine 2013;126:529

- EF < 35% (OR: 3.4)

- Ischemic background to mitral regurgitation (OR: 4.4)

- Asymptomatic patients with severe mitral regurgitation but normal EF had no increased risk

Pathophysiological aspects

- Similar pathophysiology to AI

- Volume overload of LV

- Reduced systolic function, overestimated by EF

- Pulmonary hypertension with high PVR

- RV hypertrophy

- Prominent v-wave (ventricular systole) on PCWP measurement

- Lowered SVR reduces regurgitation and increases “forward output”

- Avoid hypervolemia! Leads to further dilatation of the valve annulus and more pronounced MR

- Use PA catheter for monitoring in preoperative heart failure symptoms

Hemodynamic goals: Mitral relaps

“Faster, fuller, and vasodilated“

- Heart rate: 80-95

- Rhythm: Sinus

- Preload: Normal

- SVR: Low

- Inotropy: Normal

Anesthesia in mitral relaps

- Intubation and general anesthesia for acute mitral regurgitation (papillary muscle rupture)

- Avoid surgical stress!

- “Vasodilator anesthesia”

- Opioid + isoflurane

- Regional anesthesia

- Inodilators in low EF (milrinone, levosimendan)

- Postoperative morbidity (pulmonary edema)!!

Monitoring

- Standard 3-lead ECG, pulse oximetry

- Arterial catheter

- PAC with CCO and continuous SvO2 for severe symptomatic MR/reduced EF and high-risk surgery

- Central venous catheter with CVP measurement and continuous ScvO2

- TEE: “Recommended if acute and severe hemodynamic instability develops perioperatively” (Class I)

GUCH – An Anesthesiological Perspective

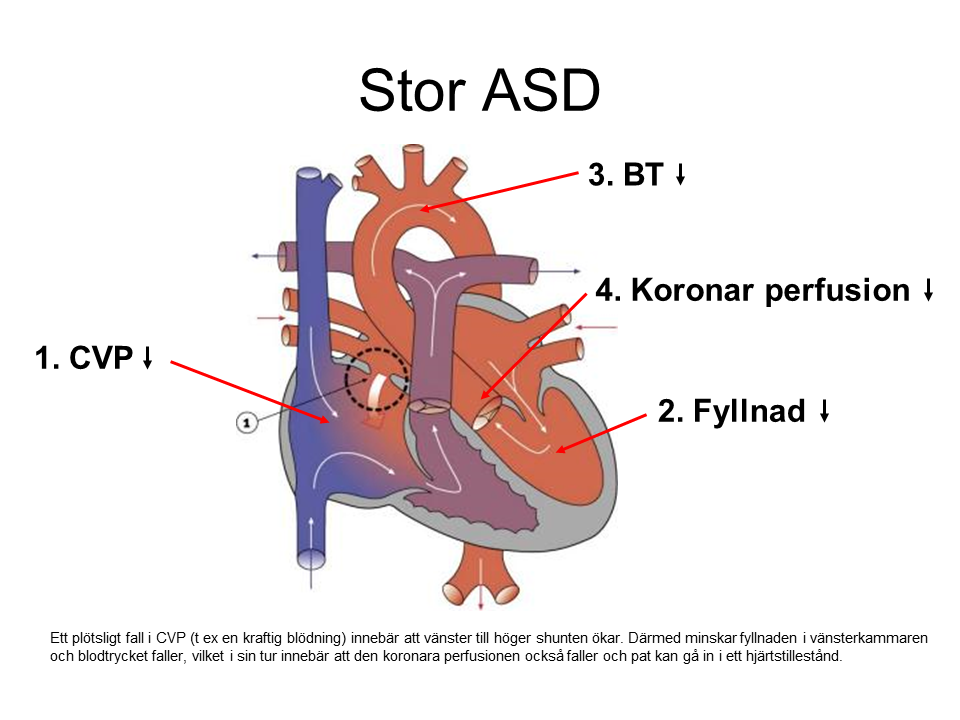

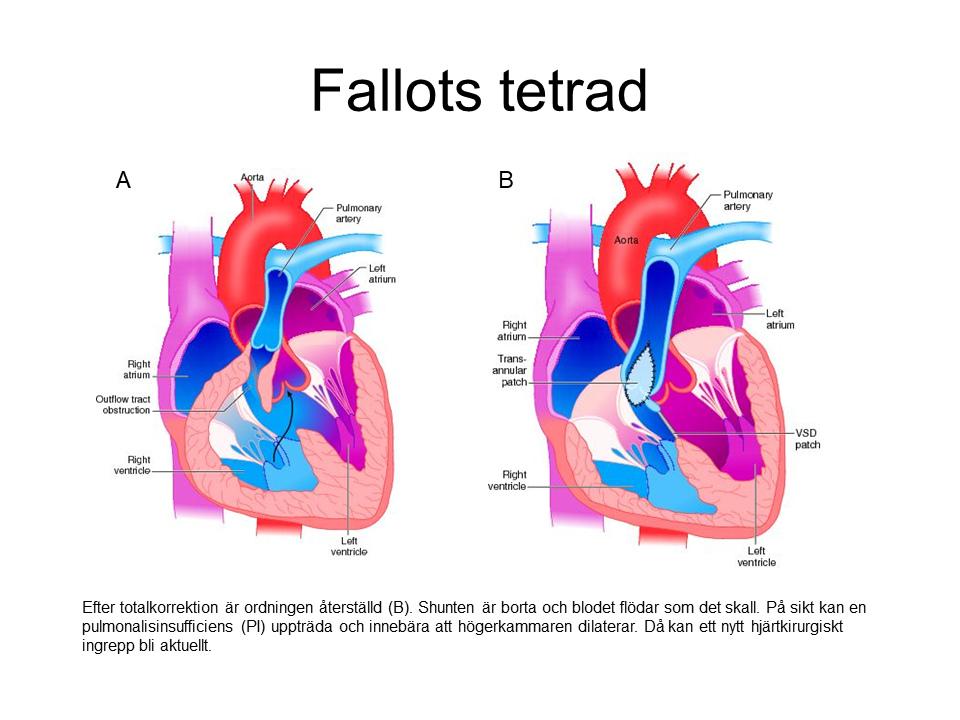

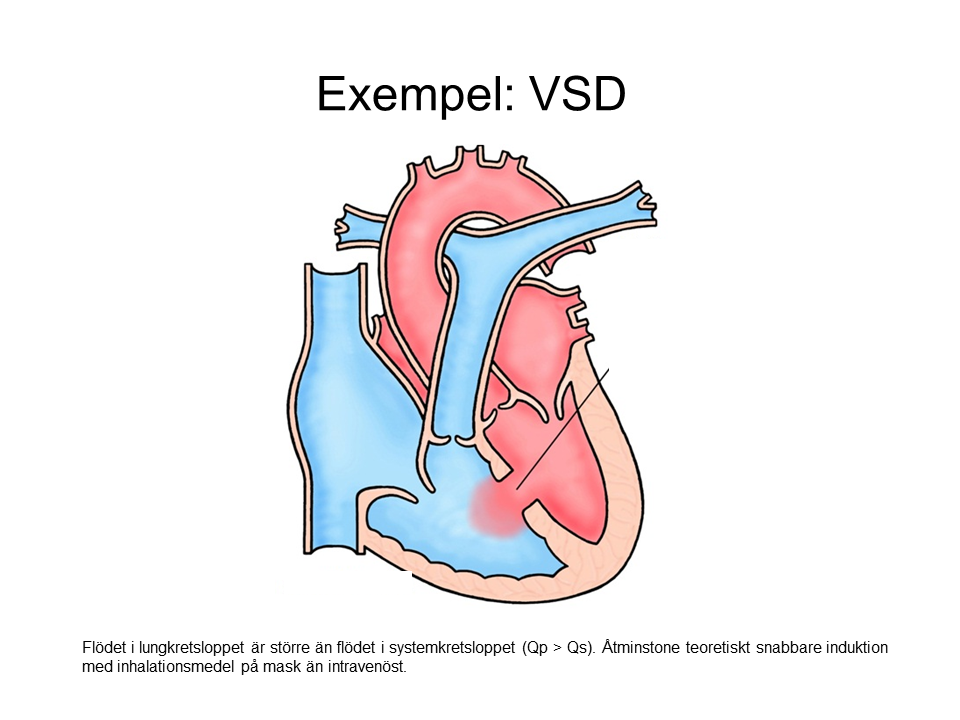

GUCH is an abbreviation for Grown Up Congenital Heart Disease, i.e., adults with congenital heart defects.

Approximately 1% of all children are born with a heart defect of varying severity, some of which require corrective heart surgery early in life. In the 1980s, a breakthrough in pediatric heart surgery, along with the development of echocardiography, resulted in more than 85% of these children surviving into adulthood. Some of these individuals will eventually require other surgeries and, consequently, anesthesia. Today, over 30,000 such individuals exist in Sweden.

From an anesthesiological perspective, the issue is that some of these patients, unfortunately, have high mortality and morbidity rates during non-cardiac surgery and childbirth. This is due to the presence of one or more of the following consequences or complications:

- Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

- Cyanosis & polycythemia

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Ventricular dysfunction

Before anesthesia for a GUCH patient, the following questions must be answered:

What type of heart defect does the patient have?

- Is the heart defect completely surgically corrected?

- Is the heart defect partially or palliatively surgically corrected?

- Is the heart defect uncorrected?

The most common heart defects

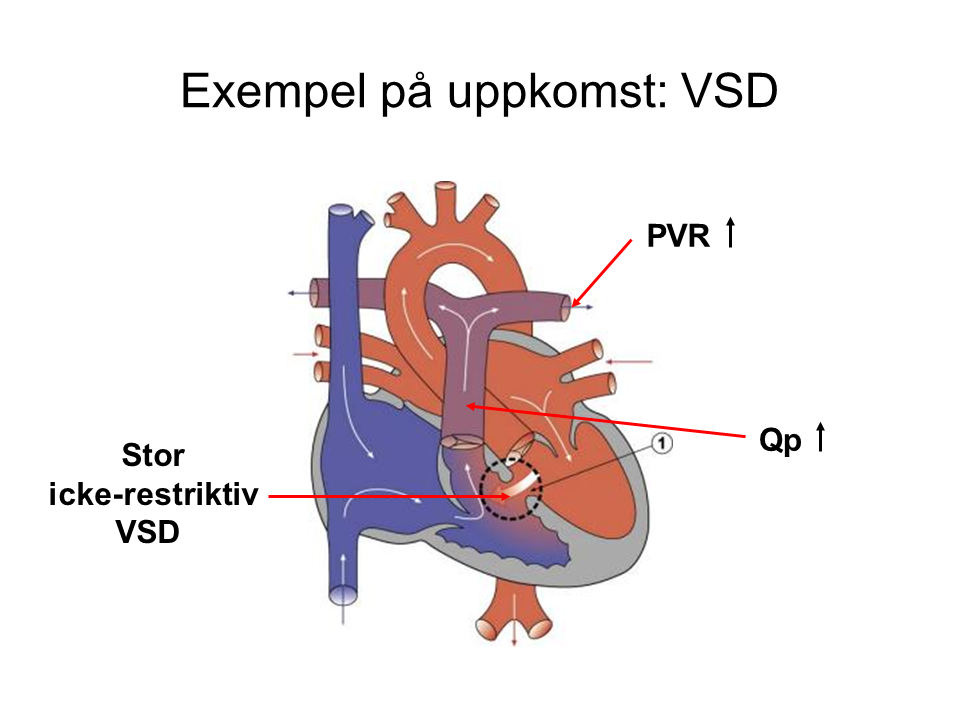

- VSD 24-35%

- Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) 6-13%

- ASD 4-11%

- AV septal defect 2-7%

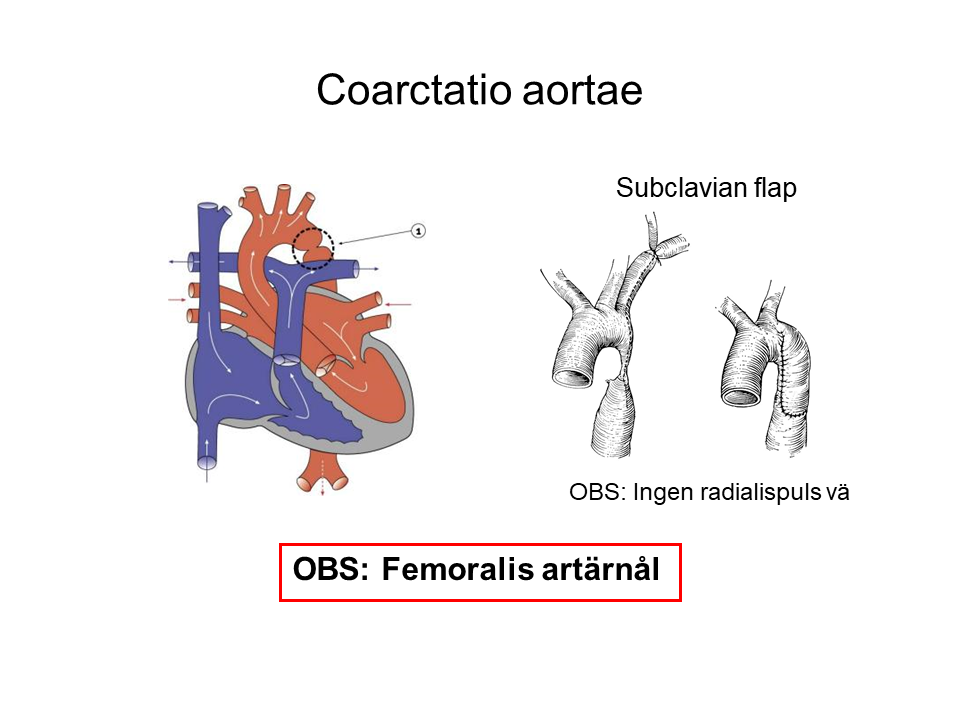

- Aortic coarctation 3-10%

- Pulmonary stenosis 3-14%

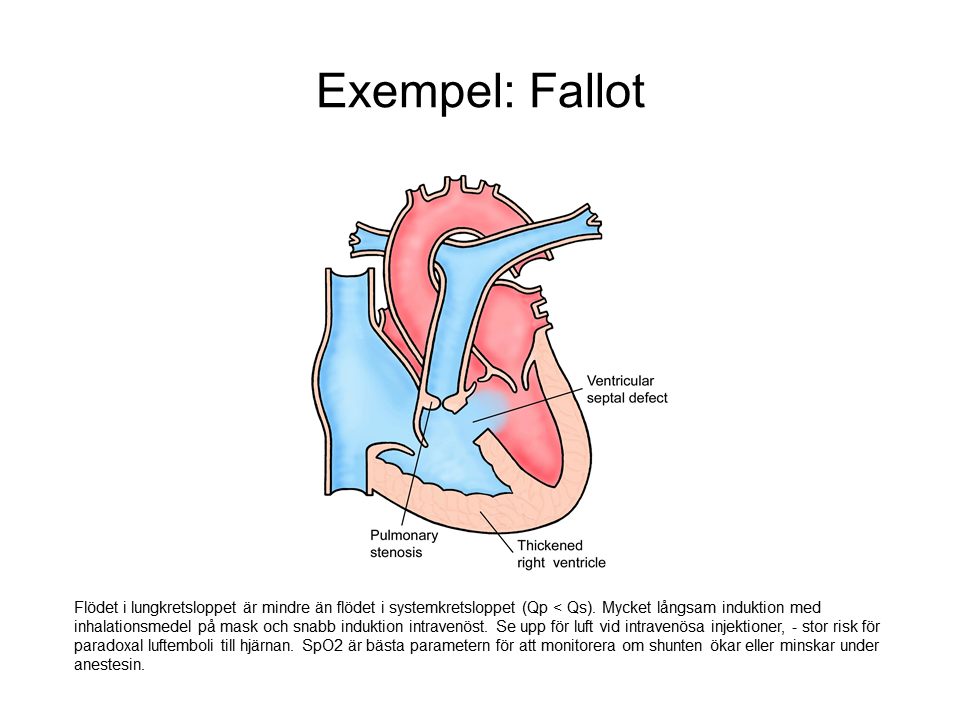

- Tetralogy of Fallot 4-8%

- Transposition 3-8%

- Pulmonary atresia 3%

How severe is the heart defect?

A “simple heart defect” can have a significant impact on hemodynamics

A “Complex Heart Defect” with Normalized Anatomy and Hemodynamics Can Be Trouble-Free

Is There a Shunt?

Left to Right Shunt (Qp > Qs)

- Intravenous induction may feel a little slower than usual.

- Mask induction may be faster than usual.

Right to Left Shunt (Qp < Qs)

- Intravenous induction may feel faster than usual.

- Mask induction takes longer than usual.

- SpO2 is lower than normal. If shunt flow increases, SpO2 drops. If shunt flow decreases, SpO2 rises.

Are Any of the Above Consequences or Complications Present?

- Consider additional pre-op evaluation.

- New UCG? Cardiology consult?

- Is the patient in optimal condition from a cardiology perspective?

- Coagulation evaluation?

- Possibly contact a GUCH center (available at all university hospitals).

Does the Patient Need Surgery?

- How strong is the indication for surgery considering the potential risk?

- Is additional evaluation needed to strengthen the indication?

Does the Patient Need Surgery Now?

- How urgent is it? (Preparation time is important)

- Should the patient be transferred to a hospital with more anesthetic resources?

- Is the patient transportable?

Monitoring During Anesthesia

- ECG

- Pulse oximeter

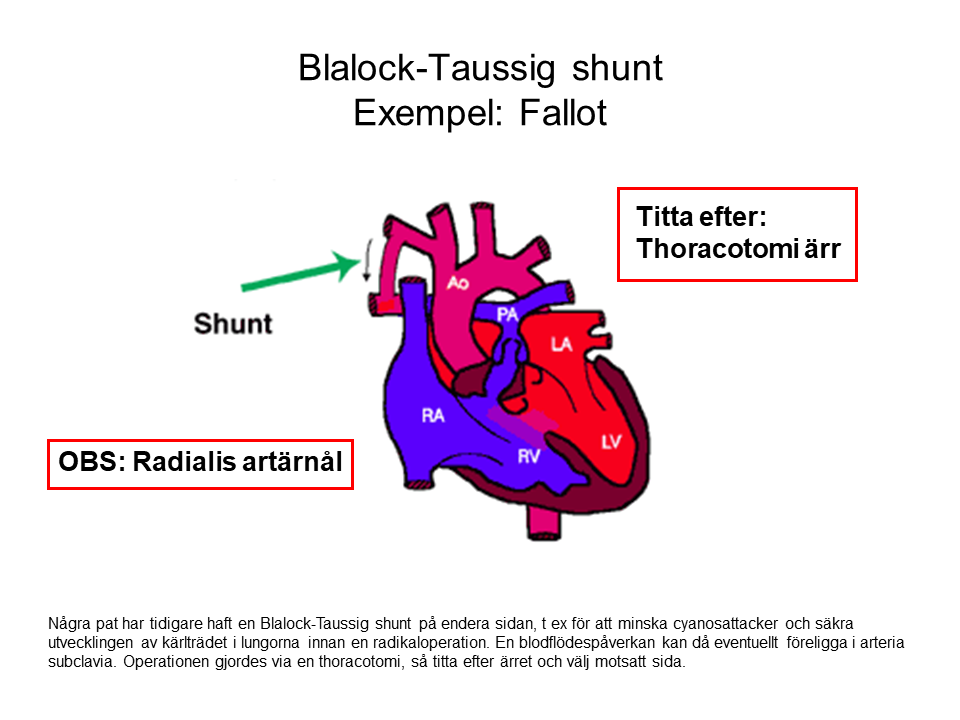

- Arterial line (be liberal), watch out for previous Blalock-Taussig shunt and previous coarctation of the aorta.

- Blood gas measurements

- End-tidal CO2 underestimates PCO2 in blood with right to left shunt (Qp < Qs).

- Possibly CVP

- Ultrasound is recommended.

- Watch out for pacemaker/ICD.

- Watch out for air in the shunt, especially right to left shunt.

- Swan-Ganz catheter, PiCCO, and TEE may be considered. It’s important to interpret the information correctly.

Treatment of Previously Mentioned Consequences or Complications:

Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH)

An increased flow in the pulmonary circulation compared to the systemic circulation (Qp > Qs) means that some patients develop vascular changes in the pulmonary circulation, raising pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). This also raises the pressure in the pulmonary circulation, placing astrain on the right ventricle. These patients may experience right heart failure during anesthesia.

Important Considerations:

- Avoid hypoxia, hypercapnia, acidosis, and hypothermia.

- Avoid opioid premedication that could impair respiration and cause hypoxia.

- A left to right shunt may reverse during induction when SVR drops, causing SpO2 to decrease. Be prepared with a vasoconstrictor: phenylephrine or norepinephrine. Watch for the increased risk of paradoxical air embolism.

- A pre-existing right to left shunt may worsen during induction due to the drop in SVR, leading to decreased SpO2. Same action as above: administer a vasoconstrictor.

- Avoid high intrathoracic pressure and high PEEP.

- Monitor and optimize right ventricular function (CVP and possibly TEE).

- Consider using pulmonary vasodilators (inhalation to avoid systemic effects)

- NO (10-40 ppm).

Eisenmenger Syndrome Is an Extreme Variant of PAH

- PVR > 10 WU or 800 dyn·s·cm-5

- Equalized pressures in the systemic and pulmonary circulations

- The VSD shunt has reversed to a right to left shunt

- SpO2 is typically 80-90%, Hgb 17-20 g/dL

- High mortality during surgery and childbirth (~25%)

- Risk of paradoxical emboli, cerebral abscesses, and pulmonary hemorrhage

- Should be managed by an anesthesiologist with extensive experience in severe PAH

Cyanosis and Polycythemia

- High risk of both bleeding and thrombosis

- Thrombocytopenia (due to peripheral consumption)

- Possibly elevated PT-INR (due to decreased vitamin K-dependent factors, V, von Willebrand)

- Consider factor concentrates or platelets

- Secondary erythrocytosis

- Increased viscosity, decreased flow velocity

- Avoid dehydration (note pre-op fasting, administer IV fluids)

- Thromboprophylaxis

- Early mobilization

Cardiac Arrhythmias

- Background

- Previous surgery on the atria may cause scarring.

- Dilated atria

- Myocardial fibrosis

- Valve insufficiency

- Treatment

- Pharmacological treatment according to standard principles.

Ventricular Dysfunction

- Background

- Pressure or volume overload

- Coronary abnormalities → myocardial ischemia

- Poor myocardial protection during previous surgery

- Impaired right ventricular function in systemic circulation

- Consequences and Treatment

- The patient often adapts, improving quality of life.

- Pharmacological treatment according to standard principles.

A Few Words About Special Conditions

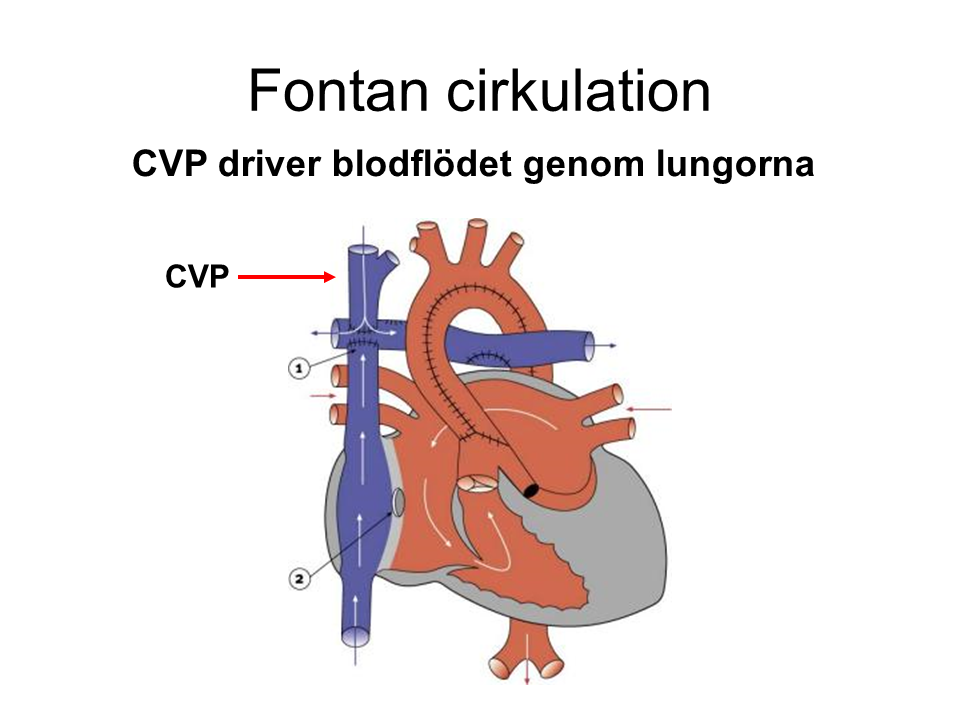

Single Ventricle/Fontan Circulation

- Background, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome

Post-Surgical Correction, Normalization in Multiple Steps

Hemodynamics in Fontan Circulation

Important Considerations

- Requires stable CV

P (usually slightly higher: 15-18 mmHg) - Watch for large perioperative bleeding and dehydration.

- Avoid hypoxia, hypercapnia, acidosis.

- Spontaneous breathing is best, but moderate positive pressure ventilation is usually tolerated. Avoid high PEEP.

- Monitor heart rhythm, sinus rhythm is ideal.

- Watch out for inhalational agents, sevoflurane > 1.5 MAC can be arrhythmogenic.

- If needed, use a pulmonary vasodilator via inhalation.

Endocarditis Prophylaxis

Recommended for (according to ESC guidelines 2015):

- General

- Previous episodes of Infective Endocarditis

- Prosthetic valve or valve repair with foreign material

- Congenital Heart Disease

- Cyanotic heart defects that have not been fully corrected

- Congenital heart defects where artificial material was used during surgery or catheter intervention – up to 6 months after the procedure

- Congenital heart defects with residual defects adjacent to the used artificial material

Not recommended for:

- Bronchoscopy, laryngoscopy, endotracheal intubation

- Gastroscopy, TEE, cystoscopy, colonoscopy

- Procedures on the skin and soft tissues

Summary

There is no universal or “gold standard” approach to anesthesia for GUCH patients. As with many other cases, each situation is unique. The key is to understand the hemodynamic consequences of the specific heart condition and to have complete control over the hemodynamic effects of the anesthetic agents used.

References and Additional Reading:

- Cannesson M, et al. Anesthesia for noncardiac surgery in adults with congenital heart disease. Anesthesiology 2009;111:432-40.

- Cannesson M, et al. Anesthesia in adult patients with congenital heart disease. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2009;22:88-94.

- Trojnarska O. Adolescents with congenital heart diseases. Cardiol J 2010;17:11-9.

- Cederholm I. Anesthesia for adult patients with congenital heart disease, GUCH. In: Lindahl S, Winsö O, Åkeson J (eds.). Anesthesia, Liber 2016:582-91.

Thoracic Anesthesia for Lung Surgery

Suspected malignancies in the lungs or already confirmed lung cancer are the most common reasons for lung surgery in Sweden. During these operations, a resection of part of the lung or, in rarer cases, the entire lung is performed. Another frequent reason for lung procedures is recurrent pneumothorax, which requires repeated drainage treatments.

Lung surgery is performed via thoracoscopy or thoracotomy. The procedure almost always requires one-lung ventilation during a significant part of the operation to ensure that the operated lung is atelectatic and remains still. A double-lumen tube or bronchial blocker is used for this purpose.

Lung separation may also be needed in other intrathoracic procedures, such as surgery on the descending aorta or esophagus, surgical correction of chest wall deformities, and certain cardiac surgeries. The technique remains the same in these cases.

Preoperative Assessment

The most important reasons for perioperative morbidity and mortality in lung surgery are respiratory complications, followed by cardiac complications. Therefore, spirometry and exercise ECG, preferably as a full ergospirometry (exercise test with gas exchange and ventilation analysis), are routinely included in the preoperative evaluation of almost all elective lung surgery patients. A CT scan of the chest is generally available and should be included in the assessment with regard to the anatomy of the trachea and bronchi.

Premedication

Premedication routines vary between clinics. Commonly used are oral base analgesics, such as paracetamol, possibly in combination with other analgesics. An opioid may be administered if the patient is not receiving a thoracic epidural (TEDA). Routine oral sedation (benzodiazepines) is generally not recommended. The most important factor is that the patient takes certain regular medications (bronchodilators, antiepileptics, beta-blockers, etc.).

Anesthesia Technique

The standard form of anesthesia is total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) with propofol and remifentanil administered via TCI pumps, combined with thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEDA). Inhalational anesthetics are generally avoided due to the risk of air leakage during surgery. The TEDA catheter is placed at the T4-T5 or T5-T6 level. The regional block is initiated preoperatively with a bolus dose of both local anesthetic and opioid. Simultaneously, an infusion with standard EDA mixture (Breivik’s mixture) or pure local anesthetic is started.

Lung Separation

Ventilatory separation of the lungs can theoretically be achieved in three different ways: single-lumen tube, double-lumen tube, or single-lumen tube with bronchial blocker.

The first option is rarely used, and only in emergencies, where severe bleeding in one lung’s airways threatens to spread to the other lung, risking the ability to ventilate the patient. If neither of the two other options is immediately available, intubating the main bronchus on the non-bleeding side with a single-lumen tube may be life-saving. This is easier on the right side by advancing the tube distally past the carina. Intubation of the left main bronchus is done using a bronchoscope as a guide.

Normally, a double-lumen tube or a single-lumen tube with a bronchial blocker is used. Both methods have advantages and disadvantages. The type of surgery and, most importantly, the ability to intubate the patient determine the choice.

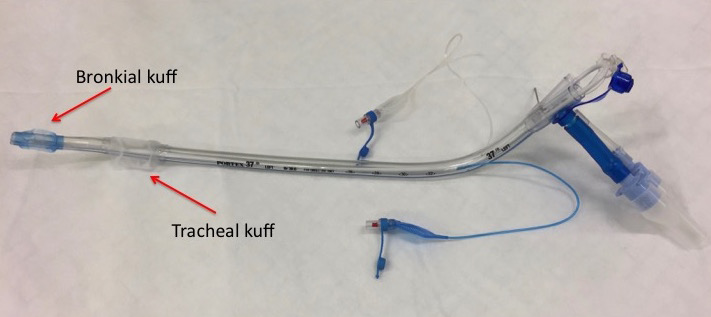

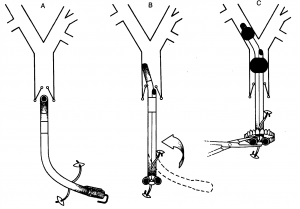

Double-Lumen Tube (DLT)

Double-lumen tubes come in two variants, right or left-curved (Figures 1 and 2), depending on whether the distal end is directed toward the right or left main bronchus. The tube has two cuffs, a larger proximal one placed in the trachea and a smaller distal one placed in one of the main bronchi. Each cuff is inflated separately using the same syringe, typically a 20 ml syringe. 3-5 ml of air is injected into the distal (bronchial) cuff and 5-8 ml into the proximal (tracheal) cuff. Additionally, the distal cuff profile differs (Figures 3 and 4). A right-sided tube also has a side hole to ensure ventilation to the right upper lobe bronchus, which arises early in the right main bronchus. In the left main bronchus, the margin from the carina to the upper lobe bronchus is 3-4 cm, so a standard olive-shaped cuff suffices.

Due to the anatomy of the right upper lobe bronchus, a right DLT is more sensitive to small positional changes intraoperatively. This contrasts with a correctly placed left DLT, which rarely dislodges. Therefore, right DLT use is typically reserved for surgeries involving left pneumonectomy or where there are anatomical changes in the left main bronchus. Left DLT is used for all other procedures.

Double-lumen tubes come in seven different sizes (Table 1), named according to their French size. The two smallest sizes are pediatric tubes. Sizes 32 to 41 are for adults. The table also shows the outer diameter in mm (divide the French size by 3).

Double lumen tube (DLT) sizes and corresponding outer diameter

| DLT French size (F) | |

|---|---|

| F size | Outer diameter (mm) |

| 26 | 8.7 |

| 28 | 9.3 |

| 32 | 10.7 |

| 35 | 11.7 |

| 37 | 12.3 |

| 39 | 13.0 |

| 41 | 13.7 |

Normally, size 35 is used for women and size 37 for men

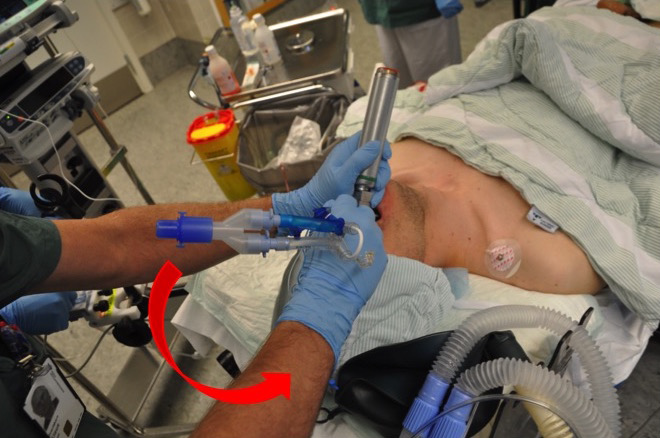

Intubation with a DLT is performed in the usual way using a laryngoscope. The accompanying guide allows the distal bronchial part of the tube to be slightly flexed, starting with the tip pointing anteriorly to facilitate intubation. Once the proximal tracheal cuff passes the vocal cords, the tube must be rotated a quarter turn counterclockwise (left tube) or clockwise (right tube) before fully advancing the tube. Figures 5 and 6 show intubation with a left tube. The guide is removed if it hasn’t been already, the tube ports are sealed, and the cuffs are inflated. At this point, the tube depth is checked using the distance markings on the side of the tube. For most patients, the distance to the front teeth is about 29 cm. Patient height plays a role, with deeper placement in taller patients and shallower placement in shorter ones.

The tube position is then checked by auscultation while testing lung isolation. When ventilation to the left lung is closed, it should be silent over the left lung field and continue ventilating sounds over the right. Then, the procedure is reversed. If everything is as expected, it is recommended to wait with bronchoscopy until the patient is turned into a lateral position, as the tube may shift during this maneuver.

Alternatively, a fiberoptic bronchoscope can be used earlier in the process. In that case, the bronchoscope is advanced through the distal bronchial part of the tube, the carina is identified, then the bronchoscope is guided into the relevant main bronchus (Fig. 7).

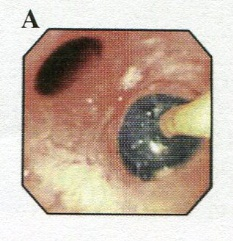

With the patient in the surgical position (usually lateral), a control bronchoscopy is performed before surgery to fine-tune the tube position. This is always done through the tracheal tube part. The carina is inspected, and just distal to it, the upper part of the bronchial blue cuff should be visible (Fig. 8).

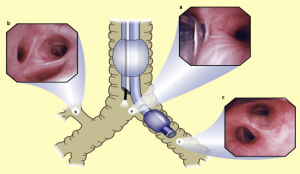

Bronchial Blockers (Bronchial Blocker)

There are at least six different brands and/or variants of bronchial blockers available. In essence, they all consist of a long catheter with an inflatable cuff at the end. By inflating the cuff in the right or left main bronchus, ventilation to the affected lung is blocked (Fig. 9).

A bronchialblocker is inserted through a single-lumen tube and positioned with the help of a fiberoptic bronchoscope. Choose the largest possible tube (size 8 or 9) to accommodate both the catheter and bronchoscope (Fig. 10).

Ventilation of One Lung

Before isolating one lung for ventilation, denitrogenation should be considered. This involves ventilating with 100% oxygen and a 6-8 liter fresh gas flow for 3-5 minutes to remove all nitrogen from the airways and the anesthesia machine circuit. This delays any shunting issues and allows the lung to collapse more quickly, which is appreciated by the surgeon.

The lung is isolated by clamping the soft tube segment leading to the side to be shut off (Fig. 11). The distal end of the tube is then opened to allow the lung to collapse (exsufflation).

During isolation, protective ventilation is recommended using pressure-controlled or pressure-guided ventilation. Aim for tidal volumes of 4-5 ml/kg adjusted body weight. Peak pressure should be under 40 cm H2O, and plateau pressure under 25 cm H2O. Typically, PEEP is set to 5 cm H2O on the ventilated lung. Permissive hypercapnia up to 8 kPa is allowed if the patient does not have right heart failure. This approach minimizes the risk of postoperative lung injury. Most patients manage with 50-70% O2 during one-lung ventilation.

If shunting problems occur (SpO2 < 90%), increasing FiO2 is the first step. If this does not help, a brief pause in surgery and temporarily inflating the isolated lung with 100% O2 can be very effective. Additionally, an O2 catheter to the isolated lung (2-5 L/min) can often improve oxygenation. Selective CPAP to the isolated lung is also an option but is rarely appreciated by the surgeon.

End of Anesthesia

At the end of the operation, the collapsed lung is re-expanded. This is most easily done manually using the anesthesia machine’s APL valve and ventilation bag. Use a gas mixture with 40% O2 and a constant pressure of a maximum of 20 cm H2O. The procedure takes 20-60 seconds. The desired effect is observed directly in the wound during thoracotomy or via the thoracoscope during thoracoscopy. Then return to normal ventilation with 30-40% O2 and PEEP 5-10 cm H2O until awakening. The patient is awakened from anesthesia in the usual way. If the patient is to remain intubated and on a ventilator, the double-lumen tube is usually replaced with a single-lumen tube before transport to the intensive care unit. A double-lumen tube should not remain in the trachea for more than a maximum of one day.

Postoperative Pain Relief

The most effective method is TEDA or paravertebral block combined with paracetamol. However, in cases of reduced coagulation ability, these techniques are contraindicated. Intercostal blockade may then be considered, but it has a shorter duration and almost always needs to be combined with an opioid. Additional medications like ketamine, clonidine, or NSAIDs may be necessary.

**Ipsilateral shoulder pain**

More than half of all patients with TEDA experience troublesome shoulder pain on the same side as the surgical procedure. This is likely “referred pain,” mediated via sensory nerve pathways in the phrenic nerve and originating from the mediastinal and diaphragmatic parts of the pleura parietale.

NSAIDs, such as ketorolac (Toradol) 15-30 mg IV, combined with paracetamol, provide the best relief for this type of pain.

References

- Benumof JL. Anesthesia for Thoracic Surgery. Saunders 1995

- Slinger P (ed). Principles and Practice of Anesthesia for Thoracic Surgery. Springer 2011

- Lohser J. Evidence-based Management of One-Lung Ventilation. Anesthesiol Clin 2008;26:241-272.

- Campos JH. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:4-10

- Campos JH. SAJAA 2008;14:22-6

Protamin

Protamine sulfate contains basic peptide sulfates that complex-bind heparin. For low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), anti-IIa activity is completely neutralized, and anti-Xa activity is partially neutralized. The degree of neutralization varies between different LMH. The effect is almost immediate.

Dosage: Bolus dose of 5 ml (50 mg) is given IV over 10 minutes, neutralizing approximately 7,000 IU of heparin. One ml of protamine neutralizes 1,400 IU of heparin. If possible, APTT or ACT (activated clotting time) should be checked immediately before and 15 minutes after administration.

Indications: Overdose and severe bleeding due to heparin or LMWH. To reverse heparin effects before emergency surgery. To neutralize heparin effects during cardiopulmonary bypass.

Concentration: Injection solution 1,400 IU/mL.

Side effects: Excessive amounts can cause bleeding and prolonged APTT.

Warning: Allergy to protamine or fish. Thrombocytopenia after cardiopulmonary bypass may worsen.

Disclaimer:

The content on AnesthGuide.com is intended for use by medical professionals and is based on practices and guidelines within the Swedish healthcare context.

While all articles are reviewed by experienced professionals, the information provided may not be error-free or universally applicable.

Users are advised to always apply their professional judgment and consult relevant local guidelines.

By using this site, you agree to our Terms of Use.